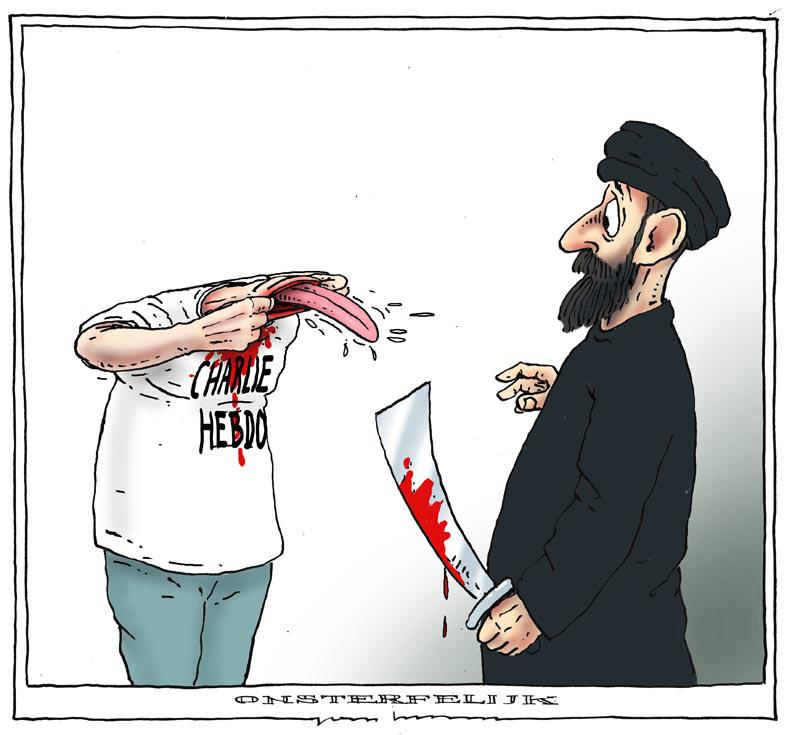

Throughout the day, as the details of the Charlie Hebdo massacre started to come to light, the truly disturbing reality of the attack really started to needle at me--these people were not killed because they lived in war-torn, unstable countries where extremism has taken such a firm hold, or because they were members of a persecuted minority; most of them weren't even killed because they were in the wrong place at the wrong time. No, mostly they were killed because they drew cartoons that offended someone. They were killed because they worked for a satirical publication that didn't back off for anyone when it came to being provocative and at times, even offensive. They were killed because the world has become such a place, that Islamic Extremism is getting more and more extreme, and the agents of their toxic ideology are becoming more and more brazen in their attacks on whomever, whenever, wherever and for whatever. I'd be terrified if I weren't so angry and heartbroken.

On my drive home from work, as I was listening to All Things Considered, they played the recording of the video caught at a nearby apartment complex on a witness' cell phone. The gun blasts somehow seemed louder, more terrifying, more filled with hate than I could remember hearing from any other violent news story that we've all become so accustomed to hearing. I jumped a bit in my seat and gripped the steering wheel a little tighter. In the fifteen minutes that it took me to drive home, they played it again. By this time, I was yelling, alone in my car, "This is such fucking bullshit!" and choking back angry tears. Somehow, this shooting wasn't just a tragic news event that should remind us all how important freedom of expression is to our social, cultural, and ultimately human well being, or that extremism in any shape and form is a vile and poisonous ideology that none of us can afford to be complacent about. Somehow, this attack felt personal.

Apparently I am not the only one who feels this way. As people around the world, from France to China, to the United States, to anywhere else you can think of took the streets to show solidarity in their belief in the right to express oneself freely without fear of being murdered, the slogan "Je Suis Charlie" popped up on signs across the globe. On my Facebook newsfeed, dozens of friends changed their avatars to "Je Suis Charlie" and article after article about the shooting was posted, and yes, even those terribly offensive cartoons that were supposedly worth killing over--it's comforting to know that those will never go away, just as free thought cannot ever be completely blotted out of the human psyche. But for me it wasn't the "I am Charlie" that made it so personal, but rather, the "Am I Charlie?"

When I was in high school, and into college in my early 20s, I was not a happy person. I was easily offended and couldn't take an off-color joke without stewing over it for days. I didn't like it when people said anything politically incorrect and saw racism, sexism and homophobia everywhere. My boyfriend at the time was like that as well. Feeling at odds with my family's political beliefs, I sought refuge in his "wisdom" and together, we fueled each other's fires of angry disdain for anyone or anything that seemed to suggest some truth about the world and the people in it that we didn't like. I would like to say that I feel that my heart was in the right place during those years, because after all, I really didn't want marginalized people to feel even more alienated in the big, bad scary world than I arrogantly assumed they must already feel. But at the root of those ultra-PC beliefs that I clung to so obsessively, beyond the B.S.of fighting "the good fight" against the tyrannical majority, down past the self-righteous indignation seething inside of me, was fear. I was the one afraid of the big, bad world, not the persecuted minorities who never asked me to be their spokesperson or agent in the first place. I was the one who couldn't completely face up to the disappointment that you come to realize when you learn that so much in the world is unjust, unfair, and simply not right. Yes, I could acknowledge that bad things happen to good people, and good things happen to bad people, but I couldn't quite face up to the fact that no matter how much I implored someone to not use that term, to not tell that joke, to not say that thing, I couldn't mold the world into my own version of what I wanted it to be. And if I could get you to not say something that offended me, then that meant I could keep on pretending that the world would one day be saved from racism, sexism, homophobia, and all other such vile things.

I was an idiot.

What has made the Charlie Hebdo shooting so personal for me, is that today, I'm staunchly against ultra-PC nonsense that seeks to censor and inhibit dialogue, free thought and expression. I welcome situations that make me think, provoke me or even make me uncomfortable and angry, because how else am I going to keep myself and what I believe in check? And here's a thought--maybe sometimes I'm wrong! Now, I can take a joke, and don't take myself and the world so deathly seriously, that you would think that I am followed by a perpetual rainy cloud, like a human Eeyore.I still have my off days, but for the most part, I've grown and changed enough to not fear being offended, to understand that there is a difference between jokes told about uncomfortable subjects at the expense of real victims, and jokes told about uncomfortable subjects to mock the often sick, ridiculous world that we live in, and the horrible place that we human beings can make it just by being our shitty selves.

Perhaps I never got to a point a of such extreme thinking that I even entertained the notion of violence against another person, but that fear, that dark, selfish, reflexive fear that the world doesn't turn according to what we want or think we need in order to feel in control and in power, is frighteningly similar to the same fear that clutches the icy heart of every extremist who would kill anyone who dares to think, feel, believe, live differently than what they would like. I want to say "I am Charlie" today, and believe that I can, but I wasn't always Charlie. Who knows what I would say today if I had managed to tumble down a different rabbit hole than the one that led me to who I am today?

Thankfully, today I can laugh. I can brush off offenses and move forward, and I have the courage to tell the people who really are offensive that they are idiots, and give elaborate examples to illustrate just exactly why, and then move on with my life when the heated conversation ends. I can be friends with people that I disagree with vehemently about things near and dear to my heart. I am closer with my family than ever before, even when I think they are wrong about something (which I obnoxiously remind them of with tedious regularity). Today I can look back at my old, angry, fearful, ridiculous self, and let her stay back in the past where she belongs. Most importantly, I can laugh at her.

Today, I can say "I am Charlie," and tomorrow, I will still be able to say it. I will say it in as many ways as I can, consequences of freedom of expression be damned, because if we don't have that, then all we have left to cling onto, is fear.

Fear is a stupid, and silly thing anyway, and should mocked at every opportunity.